Wow. Unexpected and invited gift – and a new challenge. I mean, what if I make typos and what if it is not that interesting? So, here is a start, an old story about my dad, Charles, born 1894 in the North end, then the Irish ghetto near where Logan airport is in Boston today. The Irish had just become so numerous by the end of the 1800’s and so organized that they were getting close to taking over the apparatus of the City of Boston – but it was still nearly 2 decades before that would occur. One by one, they were taking over the wards. As of 1916 my father enrolled in the only college that would accept the Irish, Boston College. He attended nights as a freshman. In the afternoons, he played football for B.C.His position was tackle and he was really good. They played with no pads and skintight leather helmets.

President Wilson gave in. The U.S. stopped just supplying shells and guns and meat to the Brits. Our army was tiny and essentially all on the Mexican border. The Navy was puny. Everyone enlisted. Training was minimal. My dad went into the Navy as a seaman, and promptly was selected for training to be a machinist’s mate on a hundred foot boat. He knew nothing about machinery. The boats were hastily mass produced and were crude things, designed to hunt subs in the North Atlantic. No aspic. No sonar. The plan was to cruise endlessly and spot a periscope (the other side didn’t have sonar either)… At that point, using signal flags, one rushed the boat to the site of the spotted periscope and four of the crew went to the stern. Depth charges were ashcan sized metal drums, packed with TNT, sealed tight and weighted. You wound up the ticker- fuse (setting it for 400 or 500 feet depths) then kicked the ashcan off the back of the boat. The boats had a crew of 18-20 and crude crew compartments. There were two 16 cylinder motors and they ran on gasoline and spewed out fumes.

Two years after the Halifax disaster ( where 5 munitions ships blew up in a Canadian harbor and flattened everything for 25 miles around) dad’s boat and a hundred others sailed for a Bermuda rendezvous with another hundred of the same. You fueled when a launch loaded with fifty gallon drums of gasoline pulled alongside and a pump and hose was inserted in a drum and some sailor turned the eggbeater handle and pumped gasoline up, cross deck, and into your tanks. With 200 boats in harbor, all needing gasoline to go to the Azores then North to Cobh (now Cork) in Southern Ireland, sloppy work on the fueling lanches led to a thick film of gas and oil on the harbor in Bermuda. Fire started late one afternoon and the slick burned furiously with choking smoke. All the boats were loaded with ashcan depth charges lashed to the decks. Every captain made haste to get out of harbor.

In Cobh (the Irish were still ruled by Britain and were giving the U.S. A Naval base there) the boats were three weeks out then I week at the base. Wherever they docked the boat, when the crew got liberty, my father was a favorite. He played the piano by ear and could play anything and could play for hours without repeating his repertoire. He did not drink so the others got free drinks while he played in bars in Ireland and in England. The usual duty was to sail East then North up through the Irish Sea, East again over the top of Britain, til on station in the Baltic, near Kiel, from which German submarines left to hunt merchant ships in the Atlantic which coming to supply the Brits and our tiny army, newly in France in the trenches. The boats operated in extreme cold with no insulated crew quarters. The Navy paid the Captains a sum to provision the boats so the crew could eat. The Captain of my dad’s boat was a drunk and a womanizer. He used up the food allowance for the crew on other pursuits and the crew was always short of food. Often, the duty was to minesweeper, as mines were sowed everywhere and were a constant danger. They were just a few feet below the surface, carefully weighted, attached to long chains with anchors below. Two of our boats would attach a chain to the stern, spread out a quarter mile apart, then proceed carefully into a minefield, spotters on the bow. The long chain would drag, then sever, the mines’ chains. The mines would bob up on the surface, floating free and pitching in the waves. A dozen boats would enter the wave-swept quarter mile full of bobbing mines. In ten degree weather, wearing pea coats, watch caps, and a mitten with one hole in it three of the crew were issued Winchester rifles and a box of ammunition. Standing on a pitching deck, they shot mines. When you hit a plunger on the mine, it exploded and a geyser of water went up.

My dad’s boat got lucky with a depth charge run. The U32 was damaged, came up onto the surface, and commenced a life or death deckgun duel with a half dozen of our boats. U32 had a 3 inch gun. Our boats had 2 inch guns each and ineffectual machine guns. My dad’s boat was hit. He worked down in the engine room which filled with choking fumes – but ceasing to man the engines was not an option. The black gang worked on in darkness and fumes to keep the boat operating and moving until U32 sank.

The boat then came down the English Channel and put in at a French port where there was a huge field hospital near the shore. Several sailors and my dad went ashore and checked in at the hospital, gassed by the fumes in the engine room from the boat having been damaged in the encounter with U32. Days passed. Bored, and feeling restored, the several crew members conferred then forged passes and went off base from the hospital to see the earlier and now emptied battlefields. The War was entering its close in 1918. The field hospital was immense and the crew members figured they would never be missed for few days.

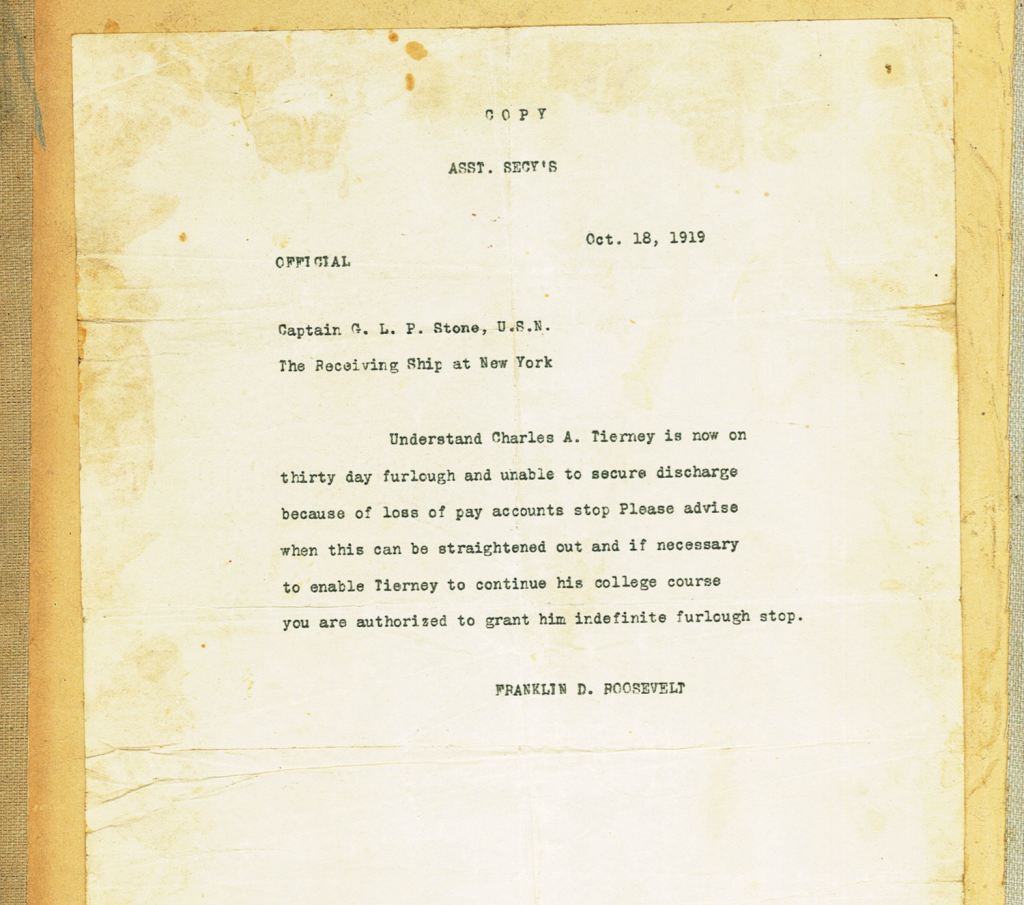

Meanwhile, my father’s father (Daniel) operated a candy and cigars store in the basement of Fanieul Hall, equidistant from the Boston City Hall and the State Legislature, about five blocks from each. He was friends with Martin Lomasney, Honey Fitzgerald, and other Boston pols, later with Mayor Curley, who was not yet on scene. President Lowell of Harvard was debating on the front page of the Boston Globe with an unknown young law professor at Harvard Law School, one Felix Frankfurter. The dialogue was whether Harvard should admit Jews and Irish “on quota”. Debate was intense but then Lowell yielded and ’twas done. Daniel went to Lowell’s office and told Lowell that he had a great tackle that Lowell could have for the asking… producing some clippings raving about my father’s prowess on the gridiron. Lowell bit – and called a young under-secretary of the Navy, one Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Roosevelt signed orders that Charles Tierney, as a matter of National security, was to be returned by ship immediately to the the Naval base in North Boston and discharged. The telegraphed orders reached France and hospital staff searched for Tierney, who could not be found for several days. When he was found, the Navy decided to make no issue of his having gotten lost for a few days… They simply shipped him home – before a hundred thousand doughboys waiting for their travel orders.

Charles Tierney’s paybook was lost but orders from Roosevelt resolved the snafu and he was discharged in time to report to the football squad in late 1918, class of 1922 at Harvard. It was a famous class at Harvard. On my wall in my office at home hangs the team picture from the 1919 Harvard Yale game. In white on the ball in front of the team, it says Harvard 9, Yale zero… In the top row, third from left is a clear eyed smiling Charles Tierney, starting a three year storied career as a star tackle. He later became the line coach at Harvard, and there is a fat book of rotogravure clippings to attest that he was a successful coach.

By the way, Frankfurter, Lowell, and Roosevelt went on to do pretty well in their own right. Charles Tierney finished at Harvard Football in 1929, went to Venezuela in ’29 on a venture involving buying Panama hats in bulk for resale to the U.S. , managed the Commander Hotel in Cambridge til 1933, managed the Harvard Business School dining halls til ’37, managed the Harvard Club in Boston from ’37 til ’51, owned and managed the Country Fare Restaurant in Hingham Massachusetts til ’62, died in 1988 at 94 years of age. In all the years after he left the Navy, he had difficulty whenever sitting in a darkened movie theatre, remembering a frightful few hours working on the engines in smoke and darkness, while his boat chased U32 around the surface of the Baltic hoping to survive a three inch deck gun’s pounding.

I saw the movie Unbroken today. It was a good account of young men doing difficult service in war. This is a story with some of the same content, just a little earlier in time.

Dave Tierney

UPDATE 12/26/14 by Sean: I haven’t taught my Dad how to use the multimedia features of WordPress yet so I’m appending these primary source materials. Below is a scan of the actual furlough order from Roosavelt that he mentioned.

And a few other awesome news clippings involving my grandfather:

And a few other awesome news clippings involving my grandfather:

- Charles Tierney has a life story like a story book

- Harvard begins to put its football fences in order

- Pic of Charles Tierney as sub center for Harvard

- “CT has exciting experiences in service – possesses unusual strengths”

- Bob Fisher names Charlie Tierney for coaching berth

- “one of the most dependable of the Cambridge forwards”

Love the blog Dave!! Wonderful first post- thanks for sharing with us 🙂 We have fun memories of the St Patricks day party at the house. Merry Christmas and Happy New Years! We look forward to checking in on your blog and also seeing Unbroken.

Wow! Great story, seriously. So fascinating that it pulled me in yesterday and I had to save the story to finish this morning. Excellent! I can’t wait to read more. Please keep writing. 🙂

Donn, if you liked the story check the updated version with the primary source materials I just added (I haven’t taught my Dad how to link or upload images yet). pretty amazing stuff.

just undrtneaeh, are usually many completely certainly not attached sites for you to our bait, having said that, they are often surely value going over